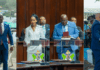

Over the past few weeks, social media and popular call-in programmes were ablaze with commentary during and after Prime Minister Philip J Pierre’s announcement that Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu would pay a state visit to Saint Lucia. The visit would include meetings with our political officials and leaders of the Organisation of the Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to discuss areas of collaboration between Nigeria and the OECS.

The commentary I encountered reminded me of my previous column, The Myth of a Raceless Society, where I argued that our country harbours deep racial prejudices, elevating whiteness as superior and blackness as inferior. These biases, rooted in enslavement and colonialism, persist in the post-independence era, masked by the myth of racial harmony, sustained by tourism economics and an unwillingness to confront the plantation mindset. Some of the reactions to the Nigerian president’s visit confirmed that this myth extends beyond our domestic politics, shaping how we view Africa and Black people globally.

However, to avoid conflating legitimate and illegitimate critiques, we must separate the substantive concerns from the muck and assess the valid arguments that should have dominated the discourse.

Logistical and economic questions

One major point of contention was the announcement by Saint Lucia Air and Sea Ports Authority (SLASPA) that both of the island’s airports would temporarily close for the president’s arrival. Many questioned this decision, noting that such measures had not been taken during previous state visits.

Their concerns—about the necessity of the closures and the potential inconvenience to visitors in our tourism-overdependent economy—were valid. These questions should have been addressed through a press conference or direct engagement by SLASPA and relevant government agencies, rather than relying on press releases and infographics, which have become a crutch (or even a weapon) when officials avoid public scrutiny.

This reflects a broader crisis in what Matthew Bishop calls “Westmonster”, where public officials, especially in the public service, neglect their duty to justify decisions. After all, it is the public service, and a persistent lack of engagement erodes trust in governance. Officials must understand that their responsibility extends beyond technocratic advice; it includes explaining decisions to the people affected by them, fostering confidence and buy-in.

Of course, the likely response would be that airport closures were necessary for security. That may be true, but the validity of a message depends not just on its content, but on how and by whom it is delivered.

Se pa sa ou fè, men mannyè ou fè’y. In a democracy, transparency and accountability are paramount. When communication is lacking, speculation and propaganda thrive.

We need a culture of justification in our politics—one that prioritises the “why” behind decisions, not just the “what”. It shouldn’t matter whether officials deem the public’s questions troublesome or partisan.

Governance requires justifying decisions to all citizens, because within the muck lies an opportunity for enlightenment, especially on issues the public has little reason to understand, given their rarity.

The overlooked economic concerns

Other critical questions, overshadowed by (I) partisan anti-intellectualism disguised as foreign policy, (II) selective outrage over Nigeria’s domestic affairs dictating our foreign relations, (III) racial prejudices, (IV) ignorance, and (V) an unfounded affinity for the West, were those about the visit’s economic cost. Was Saint Lucia bearing the full expense, or was it shared among OECS members? What was the cost-benefit analysis? These concerns cannot be dismissed.

Public funds finance government expenditures, so when citizens ask “where de money gone?”, officials must provide answers. Justifying spending builds trust in decision-making.

At every turn, we must reject the illiberal tendencies of representative democracy, where, as Rousseau noted, voting becomes both an exercise in and surrender of sovereignty. The moment we mark our X, we cede power to representatives. But democracy, as former US President Barack Obama said, is not self-executing. It requires active citizenship, regardless of who holds power.

Rahym R. Augustin-Joseph is a 24-yearold Saint Lucian pursuing his Bachelor of Laws at UWI Cave Hill, after earning first-class honours in political science and law. The current Commonwealth Caribbean Rhodes Scholar and a former UWI valedictorian, he is dedicated to using law and politics to transform Saint Lucia and the wider Caribbean.

Rahym R. Augustin-Joseph is a 24-yearold Saint Lucian pursuing his Bachelor of Laws at UWI Cave Hill, after earning first-class honours in political science and law. The current Commonwealth Caribbean Rhodes Scholar and a former UWI valedictorian, he is dedicated to using law and politics to transform Saint Lucia and the wider Caribbean.