Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping how music is written, produced, and marketed — and Saint Lucian voices are split between excitement and caution. Three industry perspectives, that of a tech consultant, a hitmaker, and a reggae artiste, are shared on the topic.

Though AI can speed up creation and cut costs, it has also forced hard questions about ownership, credit and culture. Critics argue that AI-generated songs and cloned voices risk diluting artistry and undermining copyright, while supporters see the technology as simply the next step in music’s evolution.

Local AI consultant Jim Joseph, managing director at Map and IT Solutions Ltd, says the initial backlash mirrors past shifts in music technology. “Any new technology… that tends to disrupt or impact a status quo is always [a] challenge and looked at with scepticism,” he noted, pointing to earlier leaps from live bands to synthesisers and on to streaming. As creators learn to use today’s tools, he sees “a gradual acceptance that this new technology is here to stay,” while warning that the “cloud” over rights may present issues. He points to ongoing lawsuits against music-generation platforms and debates over “what is actually fair use,” adding that court outcomes will be critical in setting precedent.

From the studio floor, award-winning musician Sherwinn Dupes Brice describes a dual feeling: “It’s exciting, and it’s scary at the same time.” For him, technology never stands still, so musicians must adapt: “You can’t get in your feelings about technology.”

What does change, he argues, is the bar for creativity and audience building: “I feel like I have to level up my game again. And I feel like the most important thing in this whole industry is marketing.” he said.

On a thornier point, AI cloning of iconic voices, his view is blunt: “Name and likeness, laws, copyright protection, publishing laws. They’re going to have to change them, bro.”

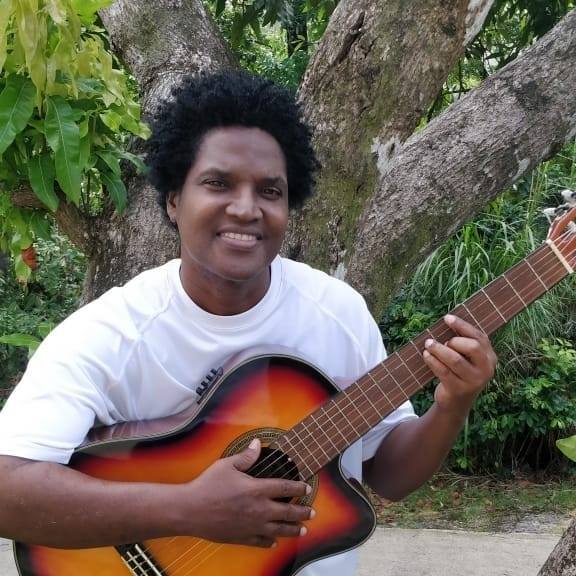

Reggae artiste Werner Semi Francis embraces AI as a craft aid, not a replacement. “I think I see it as an additional tool… I don’t think musicians should be afraid of it,” he said. The best outcomes, he adds, come when artists bring their own melodies, demos and direction: “The best results are when you have your own ideas,” using a “hybrid” approach that combines AI outputs with live elements, he said. For people worried about an AI-flooded market, his take is pragmatic: “The market has always been flooded with music,” so success still depends on song quality, business sense, and promotion.

The rights and revenue knot

Joseph stresses that copyright rules are lagging: “As far as Saint Lucia is concerned,… [copyright] has to do with material generated by a human,” which means fully AI-generated material may not qualify for protection — only the human-made parts do. He also cautions creators about platform terms. On leading music-generation sites, “by virtue of… logging into the platform,” users may “give them permission to create derivative works from your uploaded material,” potentially allowing future reuse of an artist’s uploads. “All these things are considerations,” he said.

Brice agrees that the law must evolve quickly. He cites a wider cultural discomfort with AI-revived voices and likenesses, arguing that the system will need clearer guardrails so rights-holders can opt in — or opt out — saying, “There’s a lot more policing that has to happen.”

Regional experiments are creeping in too, with Trinidad and Tobago’s first AI soca artiste JOU VAY sharing songs on social media. For Saint Lucia’s industry, that raises immediate questions: Who owns the “voice”? How are royalties split when code assists composition?

Semi sees a path that protects culture while using the tools: craft first, technology second. “You could remain very authentic with the AI because you put in your ideas… [otherwise] it will just give you something generic,” he said.

Courts, contracts, and next steps

For now, creators are working within a moving legal landscape. Joseph underlines that the “pending court cases” on training data and fair use will set important boundaries — including for small markets like Saint Lucia, where budget-friendly tools are attractive but rights must be safeguarded. “Err on the side of caution,” he advised.

Dupes’s counsel to younger artists is to adapt without losing the human core: “It’s up to me and my integrity to say, am I just going to let this machine do this or am I going to put my human element on top of it?” And whatever the tech, he adds, careers still hinge on connection: “People still want to see people in concert… Connect with each other, human connection, and find a way to tell your story.”

Semi’s advice echoes the same: build fundamentals so the tools serve the music, not the other way round. “Learn the basics… Whatever else comes in, it will just become a tool,” he said. Whether purist or hybrid, “it all boils down to knowing the music [and] knowing the business.”

For Saint Lucia’s musicians, that might be the blueprint: Embrace the efficiency, watch the contracts, and keep the human voice.